Economic theory and practice tells us that economies of scale have the

potential to increase welfare of both consumer and manufacturer. However, there

are limits to the advantages that they can bring.

It is important to be aware of

some of these. Changes in market demand, linked to large units of capital

equipment have the potential to produce high levels of output – but if demand

is at a low level, capital will be under-utilised leading to excess capacity

and rising average total costs.

Some large units of capital may

not be transferable to other uses if there is a switch in consumer demand due

either to sufficient lack of demand in other areas or operational restrictions.

This is clearly applicable to the container shipping market and the potential

for shifting fortunes in the market.

Diseconomies of scale may appear when the units of production, the very

large containerships, grow beyond the scale of production that minimises long-run

average cost. The rise in the long run average cost is caused by diseconomies

of scale. It is often difficult to pinpoint exactly the causes of diseconomies

of scale, however management theorists often point to issues related to control

of the productive units and the coordination along a large supply chain that

needs to fill a ship of 12,000 teu every week.

Let us consider an example of the 10,000

teu-12,000 teu ships, all coming on stream during a period of unprecedented

trade growth, we need to consider the above economic theories. Let’s consider

the Europe-Asia trade where the demand and volumes are sufficiently large to

sustain these ships.

A string of eight ships sailing

at around 24.5 knots with a minimal number of port calls, however the same

string travelling at 21.5 knots would

require around 40%- 50% less bunkers. Alternatively, more ports of call would

need an additional vessel, at a cost of $165m, around $50,000 per day,plus the

extra fuel costs.

The question is, at what point does the equilibrium between additional

fuel costs and asset cost break, causing a shift in the slope of economies of

scale. Have we reached this point of diminishing returns?

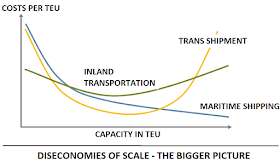

Let us look at the bigger picture – a more holistic view

Like other forms of

transportation, container shipping benefits from economies of scale in maritime

shipping, transshipment and inland transportation. The rationale of maritime

container shipping companies to have larger ships becomes obvious when the

benefits, in terms of lower costs per TEU, increase with the capacity of ships.

There is thus a powerful trend to increase the size of ships, but this may lead

to diseconomies to other components of container shipping.

For port terminals the growth in

ship capacity comes with increasing problems to cope with large amounts of

containers to be transshipped over short periods of time as shipping companies

want to reduce their port time as much as possible (improved ship asset utilization

and keeping up with schedule integrity). Larger cranes and larger quantities of

land for container operations, namely temporary warehousing on container yards,

may become prohibitive, triggering diseconomies of scale to be assumed by port

authorities and terminal operators.

For inland transportation

congestion growing capacity, such as more trucks converging towards terminal

gates, leads to diseconomies. Because of technical innovations and functional

changes in inland transportation, such as using rail instead of trucking to

move containers from or to terminals, it is unclear what is the effective

capacity beyond which diseconomies of scale are achieved.

The fundamental point is that diseconomies are a challenge that impacts

several segments of the transport chain.

Source: Hostra Edu

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.